Bryo… What?! You may not recognise the name Bryozoa, but you will almost certainly have come across these unusual animals when taking a stroll along a beach. In the UK, this would most likely be Flustra foliacea, a genus of bryozoan also known as hornwrack. Flustra foliacea is often confused with seaweed due to its broad lobed fronds, which form a ‘bushy clump’ that can grow up to 20cm tall and wide.

However, bryozoans are not seaweed, or any type of algae. They are in fact colonial animals, commonly known as “moss animals” due to the mossy appearance of the species that grow encrusting on hard surfaces, such as rocks and shells.

15,000 species of Bryozoa appear in the fossil record and there are approximately 5,000 extant species1. Whilst most are marine, there are a few species that occur in freshwater and estuaries2. The UK coastline is not the only place bryozoans are found; from the shoreline to the continental shelf, bryozoans are common wherever there is a suitable substrate to grow on. Most tend to live in shallower waters, but some species have been found as deep as 8,200m!3.

Life of Bryozoa

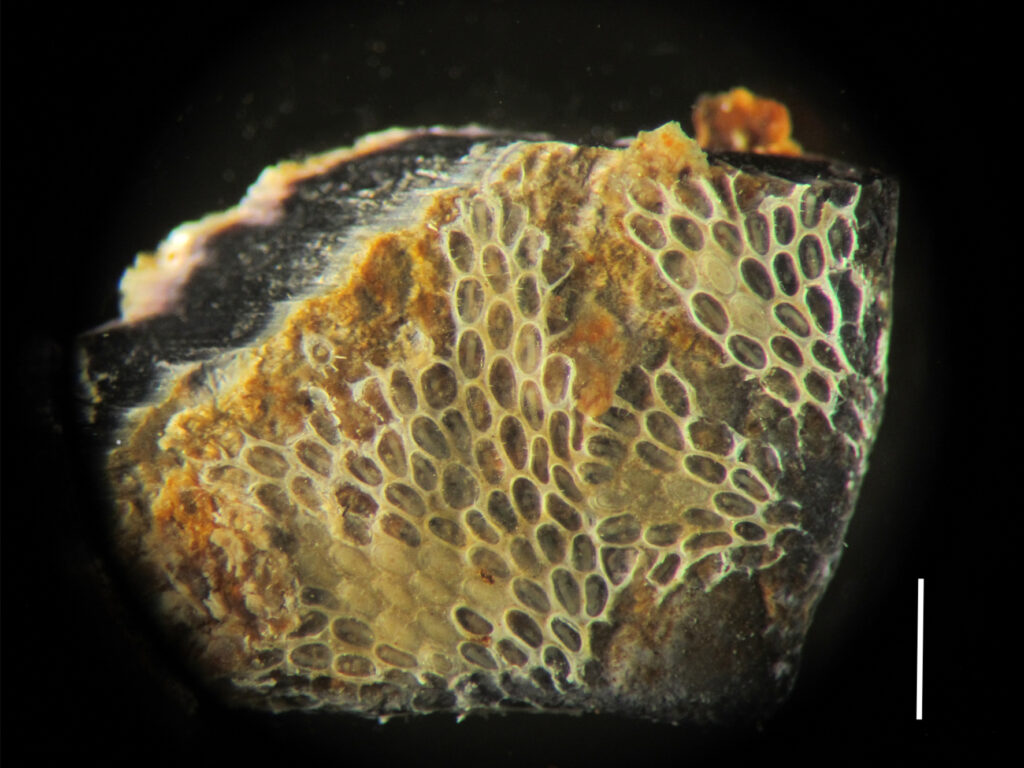

Although bryozoans are unfortunate in often being confused with other marine organisms, they are very different beasts, and are quite distinctive when observed under a microscope. Bryozoa are constructed of a colony of individual animals, zooids, which are interdependent and connected to each other through pores. Each individual zooid is tiny, at less 1 mm in length.

Colonies grow in a variety of shapes and sizes, depending on the species, including fans, bushes and encrusting sheets that grow across shells, rocks, kelp, or any other hard surface. These encrusting colonies may grow to over 50 cm and contain millions of zooids. Colonies can continue to grow for years unaffected by damage to other areas of the colony, with colony lifespans ranging from roughly 1 to 12 years.

A single zooid is the starting point for a new colony and is called an ancestrula. This sexually produced larva must encounter a suitable substrate on which to settle, where they then undergo metamorphosis, rebuilding almost all their tissues. New zooids are produced to grow a colony by asexual budding and are genetically identical to the original zooid2.

Sexual reproduction to create new colonies occurs via the release of sperm into the water column. Depending on the species, either eggs are also released into the water, or sperm are captured by female zooids using their tentacles for internal fertilization3. Bryozoa are hermaphrodites; marine species generally function as males first and then as females, with colonies containing both male and female stages.

Individual zooids can take different forms: autozooids are responsible for feeding and heterozooids can have a variety of specialized functions. Feeding generally takes place by filtering particles out of the water column using an eversible lophophore; an often horseshoe shaped collection of hollow tentacles surrounding the mouth. Cilia cover these tentacles and create a flow of water, encouraging any food floating nearby toward the mouth4.

Heterozooid specializations range from acting as brood chambers for fertilized eggs to giving the colony mobility – some species have spiny heterozooids at the edges of their colonies for burrowing and walking! Many heterozooids act to defend the colony against predation, which is vital as bryozoans have many predators including sea slugs (nudibranchs), amphipods, isopods, fish, sea urchins, and sea spiders (pycnogonids) and due to being sessile, avoiding predation is challenging. Defence strategies include heterozooids that form spines or bristles which can move around, presumably to ward off predators or clean the surface of the colony. Some heterozooids can snap at intruders and can even kill small predators or bite off appendages to deter them.

Impact

Bryozoans have had a range of quite unsavory impacts on their surroundings and on humans. A fast-growing species, Membranipora membranacea, established itself in the Gulf of Maine and covered the fronds of kelp growing there, causing them to break. This reduction in kelp cover had detrimental effects on the fauna in the area as the amount of kelp forest habitat was so significantly reduced. Bryozoans have indirectly spread diseases in fish farms, as they can act as hosts for myxozoa that cause proliferative kidney disease, which can be fatal to the fish and lead to a loss of stock. Fishermen in the North Sea have suffered from “Dogger Bank itch”, a form of eczema caused by contact with bryozoans growing on nets and lobster pots. Bryozoans are also a nuisance for humans due to biofouling, when they grow on manmade structures such as the hulls of ships and docks.

Despite these negative impacts, bryozoans also have a surprising use in medical research. Although they don’t produce any chemicals known to have medicinal benefits, one bryozoan (Bugula neritina) has a symbiont that lives within it – a bacterium called Candidatus Endobugula sertula. This endosymbiont benefits from the protection of living within the bryozoan and, in exchange, the bacteria produce a chemical that makes the bryozoan larvae unappetizing for predators. This chemical, a bryostatin, has been shown to benefit cognition in Alzheimer’s disease sufferers5.

- https://www.britannica.com/animal/moss-animal

- Hayward, P. J. and Ryland, J.S., 1999. Cheilostomatous Bryozoa, Part 2 Hippothooidea – Celleporoidea. No. 14 (Second Edition).

- https://ucmp.berkeley.edu/bryozoa/bryozoalh.html

- https://ucmp.berkeley.edu/glossary/gloss7/lophophore.html

- Sharp, K., Davidson, S. & Haygood, M. Localization of ‘Candidatus Endobugula sertula’ and the bryostatins throughout the life cycle of the bryozoan Bugula neritina. ISME J 1, 693–702 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2007.78