Contamination of the marine environment by plastic is a global issue, causing a host of problems such as microplastic ingestion by a variety of marine species, including those consumed by humans. As mussels are filter feeders, they are susceptible to accumulating pollutants from seawater and pass them up through different trophic levels, eventually entering the human food chain.

Microplastics are known to have a detrimental effect on sensitive marine species; however, mussels are robust and can thrive in polluted waters. Mussels were the first animal used to monitor chemical pollution. They make a useful bioindicator species due to their broad geographical distribution, high tolerance to environmental parameters and being easily accessible. Mussels were therefore chosen by Jalpa, one of Thomson’s Graduate Biologists, to investigate for use as a bioindicator species for microplastic pollution in UK waters.

Why Plymouth Sound?

Microplastic ingestion by mussels in the UK coastal waters was recently addressed in 2018 by Li et al. (2018). The study found all 6 sites (including Plymouth) sampled to be contaminated with micro-plastic debris. This study aims to build on Li et al’s, (2018) work, focusing on Plymouth Sound to investigate microplastic abundance and distribution, providing insight into human exposure to microplastic through ingestion.

Four sampling stations were chosen around the coastal waters of Plymouth based on 2 main factors that would best represent mussels as indicators of microplastic: how polluted the site was likely to be and the morphology of the area. The stations were separated into three categories (industrial, urban and combination) to determine if there is a correlation between microplastic distribution and the proximity of potential sources of pollution.

Sample collection, dissection and analysis

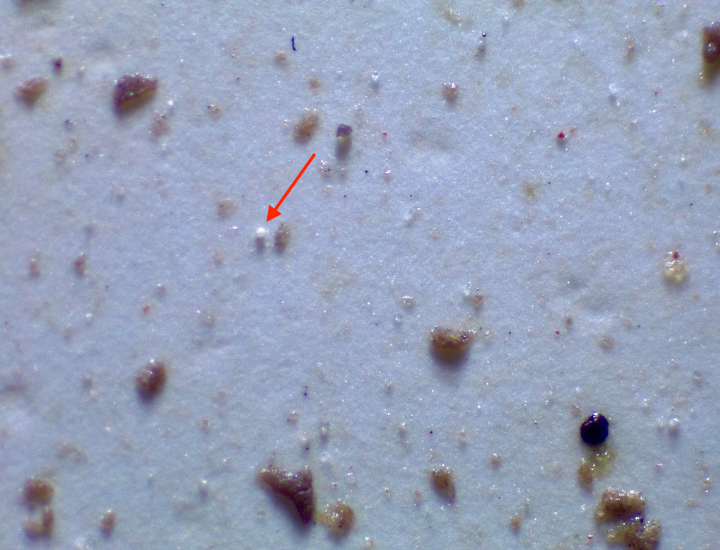

For this study, 36 mussels (Mytilus edulis) were collected during low tide from the four sampling stations. The specimens were dissected, and the stomach of the bivalve carefully excised, which then went through a chemical digestion procedure using potassium hydroxide. The digested solution was filtered through a glass microfibre filter. The samples were later analysed under the microscope for suspected microplastic based on their physical appearance.

Results

The results show microplastics were found in the tissue of 99% of the sampled mussels with an average abundance of 12.04 items per individual. Fibres (96.6%) were the most common form of microplastic identified, while pellets made up the remaining 3.3%. Neutral fibres were the most prevalent in colour (43.08%), followed by black fibres (24.42%). Significantly more microplastics were found in samples from stations close to sources of effluent run off from riverine inputs.

This study provides the first record of microplastic identified in the tissue of mussels collected from within Plymouth Sound, raising concerns for human consumption of local mussels. It also provides further evidence of the route of exposure of marine organisms to microplastics from riverine input and with continued research it will hopefully drive a human risk assessment. Whilst there are some regulations of chemical contaminants in food in the UK, the same cannot be said for microplastic. Finally, another promising line of research would be to establish mussels as a suitable bioindicator for microplastic pollution globally, to allow development of management plans to minimise human exposure to microplastic contamination.

References

1. Li J., Green C., Reynolds A., Shi H. & Rotchell M.J. (2018). Microplastics in mussels sampled from coastal waters and supermarkets in the United Kingdom. Environmental Pollution 241 (1), 35-44.

Photographic credits

Figure 1: Rachael Collins, Thomson Environmental Consultants

Figure 2: Jalpa Bariya, Thomson Environmental Consultants