As an ecologist out in the field, you must expect the unexpected. So, when two of our ecology team, Oli and Dylan, had a lucky encounter with otters – given the species’ history in the UK – it was a reminder of how important these animals are to our waterways and how vital it is to understand the impacts that developments can have on them.

The biggest surprise was that Oli and Dylan were on a bat survey, at a culvert under a busy road. When about halfway through the survey, Dylan turned to Oli and exclaimed: “otter?”

Firstly, there was disbelief. Otters are normally elusive and are rarely seen in the wild. They will usually flee upon encountering people. But to their amazement, some excitable squeaking was heard right next to them and sure enough not one, not two, but three otters were seen swimming in the concrete channel beside them – a mother and two almost fully-grown cubs.

Otters, it turns out, can also be very inquisitive animals and at the end of the survey they even walked up the bank into the open to come and have a closer look at the two humans in their territory.

Otter territory

Otters are semi-aquatic carnivores that live mostly solitary lives based along rivers, lakes and coastal areas. Their territories can be vast and size depends on the availability of their prey (which includes mainly fish, crabs and shellfish) and the width of watercourse available in which to hunt. It follows that otters along productive coastlines generally have much shorter stretches of territory than those along the banks of narrow rivers.

Otter signs

Otter spraints (droppings) have a sweet smell like jasmine tea. They use their spraints like signposts to mark their territories, they’re often found in prominent locations such as on top of large rocks and logs.

Otters mark with spraint more often when food is scarce, reinforcing their territory whilst reducing the need for potentially dangerous aggressive encounters between them. Spraints are very useful signs that ecologists look for during our otter signs surveys.

Following the survey work, Oli and Dylan informed their client of the chance otter encounter and it turned out that surveys had already found evidence of otter in the area. However, they were very surprised to hear we’d seen them on a bat survey – an unexpected piece of extra evidence.

The decline and recovery of a protected species

So, the otters were being accounted for in this case, and for good reason. The Eurasian Otter (Lutra lutra) is a European Protected Species. Therefore, otters and their habitats are fully protected in the UK by the Conservation of Habitats and Species Regulations 2017, as amended, making it an offence to deliberately capture, kill, injure or disturb them, damage or destroy a breeding site or resting place of an otter or to keep transport, sell or exchange any live or dead otter.

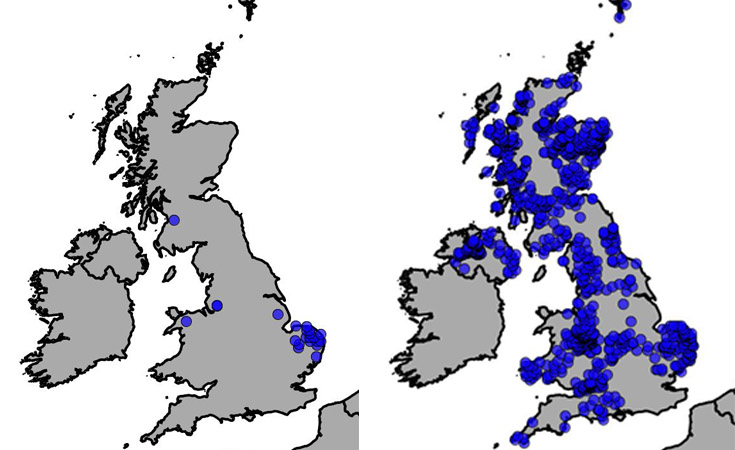

Additionally, the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 protects otters from disturbance while occupying a structure or place it uses for shelter or protection and obstructing access to such a place. In the late 1950s and 1960s otters underwent a rapid decline throughout Britain and Europe. Alongside persecution, the reasons for this decline were thought to be mainly caused by the use of the potent organochloride pesticides.

Since then, conscious efforts to clean our rivers and legal protection of this species have meant that in the most recent census published by the Environment Agency in 2011, otters were recorded in every county of the UK. This chance encounter shows that our collective efforts can and will continue to make a difference for species conservation.

How we can help you

At Thomson, our ecologists are experienced in providing Habitat Suitability Assessments (HSAs) and otter signs surveys, as well as further consultancy advice if otters may be impacted by a development. If you have a development that needs a waterway survey for otters, then get in touch with us today.